In this issue

- Background

- Survey analysis

- Access to care

- Interactions with health care providers

- Discrimination

- What does it mean for arthritis care

- Resources

JointHealth™ insight Published November 2022

Listening to you

We hope you find this information of use. Please tell us what you think by writing to us or emailing us at feedback@jointhealth.org. Through your ongoing and active participation, ACE can make its work more relevant to all Canadians living with arthritis.

Update your email or postal address

Please let us know of any changes by contacting ACE at feedback@jointhealth.org. This will ensure that you continue to receive your free email or print copy of JointHealth™ insight.

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE)

Who We Are

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) and its team members acknowledge that they gather and work on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Coast Salish peoples -ʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) operates as a non-profit and provides free research based education and information to Canadians with arthritis. We help (em)power people living with all forms of arthritis to take control of their disease and to take action in healthcare and research decision making. ACE activities are guided by its members and led by people with arthritis, scientific and medical experts on the ACE Advisory Board. To learn more about ACE, visit www.jointhealth.org

Disclosures

Over the past 12 months, ACE received grants-in-aid from: Arthritis Research Canada, Amgen Canada, Canadian Biosimilars Forum, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canadian Rheumatology Association, Eli Lilly Canada, Fresenius Kabi Canada, Novartis Canada, Organon Canada, Pfizer Canada, Sandoz Canada, Teva Canada, UCB Canada, and the University of British Columbia.

ACE also received unsolicited donations from its community members (people with arthritis) across Canada.

ACE thanks funders for their support to help the nearly 6 million Canadians living with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and the many other forms of the disease.

Disclaimer

The material contained on this website is provided for general information only. This website should not be relied on to suggest a course of treatment for a particular individual or as a substitute for consultation with qualified health professionals who are familiar with your individual medical needs. Should you have any healthcare related questions, you should contact your physician. You should never disregard medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this or any website.

This site may provide links to other Internet sites only for the convenience of World Wide Web users. ACE is not responsible for the availability or content of these external sites, nor does ACE endorse, warrant or guarantee the products, services or information described or offered at these other Internet sites.

Although the information presented on this website is believed to be accurate at the time it is posted, this website could include inaccuracies, typographical errors or out-of-date information. This website may be changed at any time without prior notice.

Health inequities and disparities in Canada exist, are persistent, and in some cases, are growing. Many of these inequities are the results of individuals’ and groups’ relative social and economic disadvantages. Inequities in health outcomes or access to care can also be systemic where disparities are observable between population groups (for example, racial or ethnic).

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) is Canada’s largest patient led arthritis group and is committed to understanding and raising awareness about inequities in arthritis care related to service delivery, treating, and managing arthritis, and self-advocacy. As part of that commitment, ACE recently conducted a national Survey to identify inequities relating to access to health care services between white and Black, Indigenous, and person of colour (BIPOC) respondents.

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) is Canada’s largest patient led arthritis group and is committed to understanding and raising awareness about inequities in arthritis care related to service delivery, treating, and managing arthritis, and self-advocacy. As part of that commitment, ACE recently conducted a national Survey to identify inequities relating to access to health care services between white and Black, Indigenous, and person of colour (BIPOC) respondents.

Background

Background

Research has shown that BIPOC and underserved populations are at greater risk of having arthritis diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, and experience higher disease activity than white populations1,2. These differences do not occur by chance. Instead, they are the result of an interwoven combination of socioeconomic and cultural factors. Differences in access and treatment are rooted in a history of racism, discrimination, power imbalances, and cultural differences3, especially for Indigenous Peoples4. A recent Canadian study that followed 7720 visible minorities and immigrants found that those who faced discrimination and unfair treatment were more likely to experience a decline in self-reported health status5. While the World Health Organization and federal and provincial governments in Canada have written reports and made calls-to-action6, little has been done at the community, regional, and provincial levels to address health inequities in meaningful ways for Canadians.

How the Survey was conducted

ACE conducted a 33-question online Survey (Aug 2-19, 2022) in English and French. The Survey was conducted in partnership with Research Co., a public polling firm. Respondents answered questions regarding population characteristics, access to care, interactions with health care providers, unfavourable experiences, and information seeking habits.

Survey analysis

Survey analysis was conducted for three Survey groups:

A total of 1,249 responses were received.

Education and socioeconomic status

From our Survey responses, Indigenous Peoples reported less formal education compared to white respondents. Black and people of colour reported similar levels of education as white respondents. Overall, no differences in income were observed between BIPOC and non-BIPOC respondents (Please note that individuals who complete online surveys tend to have higher indicators of socioeconomic status*).

*Please refer to the Addendum at the bottom of the page

Access to Care

Access to Care

Timely diagnosis and treatment for people with arthritis varies widely across Canada. Research shows that delays in accessing appropriate treatment and care can result in higher rates of disability, increased joint damage, increased pain, and significant reduction in quality of life.

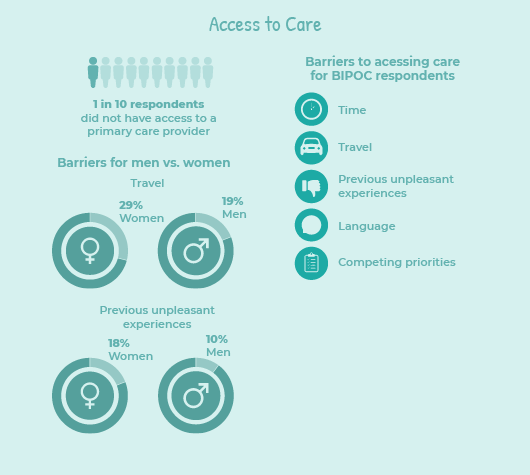

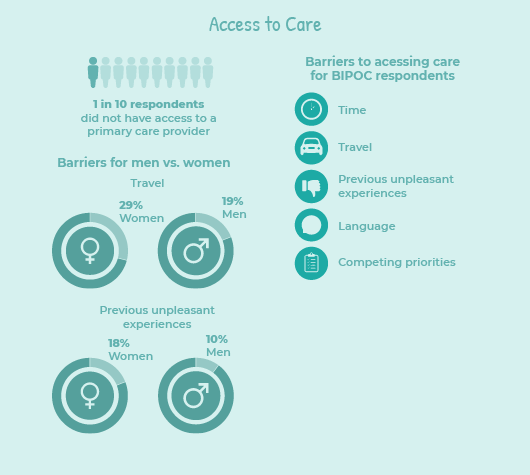

ACE’s Survey findings highlight the urgent need to address these health care needs and create equitable care. One in 10 Survey respondents did not have access to a primary care provider. Survey respondents who were Black, Indigenous, or a person of colour, women, and individuals living in rural areas experienced disproportionate challenges in accessing health care:

“Geography. I live in a remote community and it makes accessing healthcare difficult.”

– Indigenous respondent living in a rural community

“Some places are not physically accessible or don’t have virtual options. Also a lot of times they can only be reached by phone and they do not pick up or their office staff is incompetent.”

– Person of colour respondent

“Provider has no available appointments for months or weeks.”

– Black respondent

Traditional medicines and practices

Traditional medicines and practices

Medicinal plants have been used in traditional healthcare systems for centuries. A study published in the Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine estimated that 70-80% of people worldwide rely on traditional herbal medicine to meet their primary health care needs7. Through trial and error over time, Indigenous Peoples have gained a vast knowledge of medicinal plants; this knowledge is passed down from generation to generation.

Our Survey asked if health care provider included traditional medicines and practices into their care and treatment recommendations. Amongst the Indigenous respondents, half said “yes” and half said “no”.

What respondents told us:

“They don’t do anything like this. Just prescribe pills for pain.”

– Indigenous respondent

“They are tolerant of the other methods I employ to manage my condition and take a well “if it works” kind of position towards it.”

– Indigenous respondent

“She incorporates recommendations and asks how I feel about limiting prescription medication and try natural methods first.”

– Black respondent

Interactions with health care providers

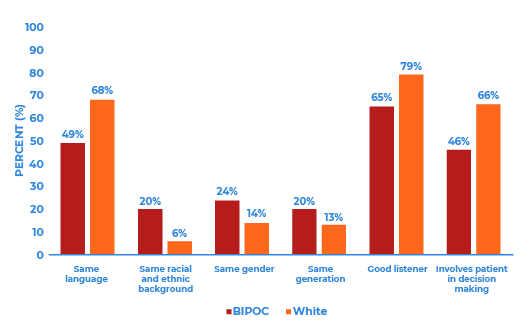

ACE’s Survey findings show that interactions with primary care providers were rated less favourable by BIPOC respondents. Results were even more pronounced when asked to rate interactions with a rheumatologist.

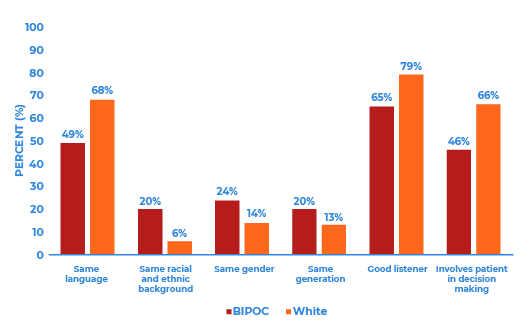

When asked which characteristics they looked for in health care providers (HCP), significant differences were revealed [Figure A]. BIPOC respondents reported favoring HCPs with the same racial background, gender, or generation. Good listening skills, involving the patient in decision making and speaking the same language were also valued by BIPOC respondents, but less by white respondents.

When compared to men, women rated interactions with primary care providers similarly, but rheumatologists less favourably. Eight in 10 women reported valuing good listening skills and 7 in 10 being involved in decision making, which is significantly more than men. The greatest differences occur in accessibility – 6 in 10 of women (vs half of men), and virtual care – 4 in 10 women (vs 2 in 10 of men).

Figure A: What characteristics patients seek in health care providers

Topics discussed with rheumatologist

Topics discussed with rheumatologist

When asked if they felt comfortable speaking to their rheumatologist about different topics, ACE’s Survey found that:

“Was comfortable with my Rheumatologist as they were understanding, a good listener, caring. This doctor happened to be in the same age group and was sympathetic towards Indigenous people.”

– Indigenous respondent

“I waited a long time and when I followed up with my referral, they told me my appointment was the next day and if I couldn't make it I would have to wait another 3 months to get in. They mailed to the wrong address and were downright rude explaining this. I did not have access to a vehicle that day and the rheumatologist told me to just take the bus. As if that is something everyone has access to and I should drop everything for their appointment. They were wearing jean shorts and a Hawaiian shirt and were very standoffish and unprofessional, could not get me out of their office fast enough and this is the one specialist in my province. I was told I have very minimal OA, nothing can be done and that it would be good if I lost a few pounds. I am overweight and am told this at every single appointment.”

– Black respondent

“The appointments are rushed. My last appointment she was in the room with me for 2 minutes and then had someone from her staff (not a rheumatologist) finish the appointment with me. A lot of my concerns are dismissed and I’m always told that nothing can be done for me and I should accept a life with pain.”

– POC respondent

Discrimination

Discrimination

The Survey asked respondents how often they experience discrimination based on their race or ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation. BIPOC respondents were six times as likely to report having experienced ethnicity-based discrimination “often” (13%), when compared to white respondents (2%). Results were even more pronounced for Indigenous Peoples who face discrimination “often” based on ethnicity (25% vs 2%), gender (21% vs 5%), and sexual orientation (15% vs 2%). Other findings include:

“Sometimes as an aging person I feel that my conditions are downplayed because I am old. Corrective surgery is not encouraged or further investigation is not asked for unless I am willing to have surgery. in a younger person the referrals would be made even if they did not result in surgery.”

– Indigenous respondent

“Experienced discrimination and prejudice about being a recovering addict, about my choices in relationships, about being a rape victim, about growing up in foster care, about foster care not seeking proper medical care for me.”

– Black respondent

“I was given a skin whitening cream by a dermatologist who said people with darker skin sometimes get darker patches of skin on them and completely ignored tell-tale signs of insulin resistance and dismissed me within 5 minutes. Also told me that exercise would be good (even though I said I already was doing it).”

– Black respondent

“I am bisexual but my relationship is straight passing so it does not cause any issues. I am non-binary and haven't told all my care providers but to the ones I have told, I am still misgendered often. Most of my doctors now are not racially discriminatory but I have experienced it in the past with hospital emergency doctors and by nurses and administration staff.”

– POC respondent

“I am East Asian and my doctor is located in a predominantly Caucasian, lower-income neighborhood. Even though I’m born in Canada, when I visit my doctors office, people treat me as if I’m new to the country. Nurses taking my blood are so rude to me.”

– POC respondent

Information seeking habits

Information seeking habits

Finding credible information about your type of arthritis is an important part to self-care and managing physical and psychological symptoms. Our Survey found that: What does it mean for arthritis care

What does it mean for arthritis care

Our findings suggest that BIPOC respondents face significantly greater barriers when accessing arthritis care, and when they do, benefit less from their interactions. ACE’s Survey results further reinforce current health literature that calls for training HCPs to create safe spaces, meaningfully address patient concerns and ensure the delivery of equitable care.

Resources to help build a culturally safe space:

Addendum

`

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) is Canada’s largest patient led arthritis group and is committed to understanding and raising awareness about inequities in arthritis care related to service delivery, treating, and managing arthritis, and self-advocacy. As part of that commitment, ACE recently conducted a national Survey to identify inequities relating to access to health care services between white and Black, Indigenous, and person of colour (BIPOC) respondents.

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) is Canada’s largest patient led arthritis group and is committed to understanding and raising awareness about inequities in arthritis care related to service delivery, treating, and managing arthritis, and self-advocacy. As part of that commitment, ACE recently conducted a national Survey to identify inequities relating to access to health care services between white and Black, Indigenous, and person of colour (BIPOC) respondents. Background

BackgroundResearch has shown that BIPOC and underserved populations are at greater risk of having arthritis diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, and experience higher disease activity than white populations1,2. These differences do not occur by chance. Instead, they are the result of an interwoven combination of socioeconomic and cultural factors. Differences in access and treatment are rooted in a history of racism, discrimination, power imbalances, and cultural differences3, especially for Indigenous Peoples4. A recent Canadian study that followed 7720 visible minorities and immigrants found that those who faced discrimination and unfair treatment were more likely to experience a decline in self-reported health status5. While the World Health Organization and federal and provincial governments in Canada have written reports and made calls-to-action6, little has been done at the community, regional, and provincial levels to address health inequities in meaningful ways for Canadians.

How the Survey was conducted

ACE conducted a 33-question online Survey (Aug 2-19, 2022) in English and French. The Survey was conducted in partnership with Research Co., a public polling firm. Respondents answered questions regarding population characteristics, access to care, interactions with health care providers, unfavourable experiences, and information seeking habits.

Survey analysis

Survey analysis was conducted for three Survey groups:

- Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC) respondents versus white respondents

- Rural respondents versus non-rural respondents

- Women respondents versus men respondents vs non-binary respondents

A total of 1,249 responses were received.

- A quarter of respondents identified as BIPOC and three quarters of respondents identified as white*.

- 3 in 5 respondents identified as women, 2 in 5 as men, and 1 in 100 as non-binary. Almost half of the Indigenous respondents identified as Two-spirited.

- 54% of respondents lived in urban areas; while 37% lived in suburban or rural areas.

Education and socioeconomic status

From our Survey responses, Indigenous Peoples reported less formal education compared to white respondents. Black and people of colour reported similar levels of education as white respondents. Overall, no differences in income were observed between BIPOC and non-BIPOC respondents (Please note that individuals who complete online surveys tend to have higher indicators of socioeconomic status*).

*Please refer to the Addendum at the bottom of the page

Access to Care

Access to CareTimely diagnosis and treatment for people with arthritis varies widely across Canada. Research shows that delays in accessing appropriate treatment and care can result in higher rates of disability, increased joint damage, increased pain, and significant reduction in quality of life.

ACE’s Survey findings highlight the urgent need to address these health care needs and create equitable care. One in 10 Survey respondents did not have access to a primary care provider. Survey respondents who were Black, Indigenous, or a person of colour, women, and individuals living in rural areas experienced disproportionate challenges in accessing health care:

- Compared to white respondents, BIPOC reported greater barriers to accessing care including time (40%), travel (31%), previous unpleasant experiences (21%), language (20%), and competing priorities (19%).

- Women reported greater barriers than men including travel (29% vs 19%), and previous unpleasant experiences (18% vs 10%).

- Respondents living in rural areas experienced even greater travel related barriers. Indigenous Peoples who resided in rural communities experience the greatest challenge.

“Geography. I live in a remote community and it makes accessing healthcare difficult.”

– Indigenous respondent living in a rural community

“Some places are not physically accessible or don’t have virtual options. Also a lot of times they can only be reached by phone and they do not pick up or their office staff is incompetent.”

– Person of colour respondent

“Provider has no available appointments for months or weeks.”

– Black respondent

Traditional medicines and practices

Traditional medicines and practicesMedicinal plants have been used in traditional healthcare systems for centuries. A study published in the Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine estimated that 70-80% of people worldwide rely on traditional herbal medicine to meet their primary health care needs7. Through trial and error over time, Indigenous Peoples have gained a vast knowledge of medicinal plants; this knowledge is passed down from generation to generation.

Our Survey asked if health care provider included traditional medicines and practices into their care and treatment recommendations. Amongst the Indigenous respondents, half said “yes” and half said “no”.

What respondents told us:

“They don’t do anything like this. Just prescribe pills for pain.”

– Indigenous respondent

“They are tolerant of the other methods I employ to manage my condition and take a well “if it works” kind of position towards it.”

– Indigenous respondent

“She incorporates recommendations and asks how I feel about limiting prescription medication and try natural methods first.”

– Black respondent

Interactions with health care providers

ACE’s Survey findings show that interactions with primary care providers were rated less favourable by BIPOC respondents. Results were even more pronounced when asked to rate interactions with a rheumatologist.

When asked which characteristics they looked for in health care providers (HCP), significant differences were revealed [Figure A]. BIPOC respondents reported favoring HCPs with the same racial background, gender, or generation. Good listening skills, involving the patient in decision making and speaking the same language were also valued by BIPOC respondents, but less by white respondents.

When compared to men, women rated interactions with primary care providers similarly, but rheumatologists less favourably. Eight in 10 women reported valuing good listening skills and 7 in 10 being involved in decision making, which is significantly more than men. The greatest differences occur in accessibility – 6 in 10 of women (vs half of men), and virtual care – 4 in 10 women (vs 2 in 10 of men).

Figure A: What characteristics patients seek in health care providers

Topics discussed with rheumatologist

Topics discussed with rheumatologistWhen asked if they felt comfortable speaking to their rheumatologist about different topics, ACE’s Survey found that:

- BIPOC respondents were less comfortable speaking with their rheumatologist about discomfort (29%) and medications (24%).

- Only one quarter of men reported being comfortable asking about discomfort (27%), and a third (35%) about pain, and a fifth about medication (21%). In addition, less than 16% of male respondents were comfortable speaking to rheumatologists about anxiety and depression.

“Was comfortable with my Rheumatologist as they were understanding, a good listener, caring. This doctor happened to be in the same age group and was sympathetic towards Indigenous people.”

– Indigenous respondent

“I waited a long time and when I followed up with my referral, they told me my appointment was the next day and if I couldn't make it I would have to wait another 3 months to get in. They mailed to the wrong address and were downright rude explaining this. I did not have access to a vehicle that day and the rheumatologist told me to just take the bus. As if that is something everyone has access to and I should drop everything for their appointment. They were wearing jean shorts and a Hawaiian shirt and were very standoffish and unprofessional, could not get me out of their office fast enough and this is the one specialist in my province. I was told I have very minimal OA, nothing can be done and that it would be good if I lost a few pounds. I am overweight and am told this at every single appointment.”

– Black respondent

“The appointments are rushed. My last appointment she was in the room with me for 2 minutes and then had someone from her staff (not a rheumatologist) finish the appointment with me. A lot of my concerns are dismissed and I’m always told that nothing can be done for me and I should accept a life with pain.”

– POC respondent

Discrimination

DiscriminationThe Survey asked respondents how often they experience discrimination based on their race or ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation. BIPOC respondents were six times as likely to report having experienced ethnicity-based discrimination “often” (13%), when compared to white respondents (2%). Results were even more pronounced for Indigenous Peoples who face discrimination “often” based on ethnicity (25% vs 2%), gender (21% vs 5%), and sexual orientation (15% vs 2%). Other findings include:

- Men reported experiencing discrimination based on race and ethnicity (7%), and sexual orientation (2%) twice as frequently than women (3% and 2% respectively).

- Women (8%) reported experiencing discrimination based on gender twice as often as men (4%).

- No differences were detected between rural and non-rural respondents.

“Sometimes as an aging person I feel that my conditions are downplayed because I am old. Corrective surgery is not encouraged or further investigation is not asked for unless I am willing to have surgery. in a younger person the referrals would be made even if they did not result in surgery.”

– Indigenous respondent

“Experienced discrimination and prejudice about being a recovering addict, about my choices in relationships, about being a rape victim, about growing up in foster care, about foster care not seeking proper medical care for me.”

– Black respondent

“I was given a skin whitening cream by a dermatologist who said people with darker skin sometimes get darker patches of skin on them and completely ignored tell-tale signs of insulin resistance and dismissed me within 5 minutes. Also told me that exercise would be good (even though I said I already was doing it).”

– Black respondent

“I am bisexual but my relationship is straight passing so it does not cause any issues. I am non-binary and haven't told all my care providers but to the ones I have told, I am still misgendered often. Most of my doctors now are not racially discriminatory but I have experienced it in the past with hospital emergency doctors and by nurses and administration staff.”

– POC respondent

“I am East Asian and my doctor is located in a predominantly Caucasian, lower-income neighborhood. Even though I’m born in Canada, when I visit my doctors office, people treat me as if I’m new to the country. Nurses taking my blood are so rude to me.”

– POC respondent

Information seeking habits

Information seeking habitsFinding credible information about your type of arthritis is an important part to self-care and managing physical and psychological symptoms. Our Survey found that:

- BIPOC respondents more often turn to family, friends, coworkers, traditional healers, and elders for health information.

- Compared to men, women more often seek information from rheumatologists (38% vs 28%), others with a similar type of arthritis (29 vs 17%), patient organizations (18% vs 10%), and websites (72% vs 53%).

- Rural and non-rural respondents sought out information from similar sources.

- Black (55%), Indigenous (54%) and POC (43%) respondents were more likely to find online information to be “helpful” and all preferred resources recommended by family and close friends with culturally sensitive content. In contrast to white respondents (66%), less BIPOC (51%) viewed official public health websites as trustworthy.

- Men and women found online information to be “helpful” (40% and 39%), but women preferred official public health sites and those run by health advocacy groups with a high-rank on search engines and have other indicators of credibility.

What does it mean for arthritis care

What does it mean for arthritis careOur findings suggest that BIPOC respondents face significantly greater barriers when accessing arthritis care, and when they do, benefit less from their interactions. ACE’s Survey results further reinforce current health literature that calls for training HCPs to create safe spaces, meaningfully address patient concerns and ensure the delivery of equitable care.

Resources to help build a culturally safe space:

- Arthritis At Home: Equity and biases in rheumatology care with Dr. Diane Lacaille

- Arthritis At Home: Racism Against Indigenous Peoples in Alberta ER

- Cultivating Cultural Safety in Your Clinic: A Toolkit for Kootenay Boundary Practitioners

- Culturally Safe Care: Resources for health care workers

- Indigenous Engagement and Cultural Safety Guidebook: A Resources for Primary Care Networks

- First Nations Health Authority: Cultural Safety and Humility

- Assembly of First Nations It's Our Time Education Toolkit: Cultural Competency

- Saskatchewan Health Authority: Cultural Competency and Cultural Safety Toolkit

- First Nations and Metis Health: Cultural Competency and Safety Resource Centre

- San'yas Indigenous Cultural Safety Training Program

| 1 | Greenberg, J. D., Spruill, T. M., Shan, Y., Reed, G., Kremer, J. M., Potter, J., Yazici, Y., Ogedegbe, G., & Harrold, L. R. (2013). Racial and ethnic disparities in disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. American Journal of Medicine, 126(12), 1089–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.09.002 |

| 2 | Hitchon, C. A., Khan, S., Elias, B., Lix, L. M., & Peschken, C. A. (2020). Prevalence and incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in canadian first nations and non-first nations people: A population-based study. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology, 26(5), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000001006 |

| 3 | Lavoie, J. G., Kornelsen, D., Wylie, L., Mignone, J., Dwyer, J., Boyer, Y., Boulton, A., & O’donnell, K. (2016). Responding to health inequities: Indigenous health system innovations. In Global Health, Epidemiology and Genomics (Vol. 1, p. e14). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/gheg.2016.12 |

| 4 | Merlan, F. (2009). Indigeneity: Global and local. Current Anthropology, 50(3), 303–333. https://doi.org/10.1086/597667 |

| 5 | de Maio, F. G., & Kemp, E. (2009). The deterioration of health status among immigrants to Canada. http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1080/17441690902942480, 5(5), 462–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441690902942480 |

| 6 | WHO. (2021). Health equity and its determinants. World Healh Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/health-equity-and-its-determinants |

| 7 | Uprety, Y., Asselin, H., Dhakal, A. et al. Traditional use of medicinal plants in the boreal forest of Canada: review and perspectives. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 8, 7 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-8-7 |

Addendum

| Ethnic origin* | |

| East Asian European Latin American South Asian Southeast Asian Middle Eastern Other |

71 (6%) 772 (62%) 49 (4%) 55 (4%) 38 (3%) 32 (3%) 153 (12%) |

| *Percentages do not add to 100% due to missing values and/or round off. | |

| Education* | |

|

Less than high school High school or equivalent Some college or university College or university graduate |

47 (4%) 227 (18%) 292 (23%) 572 (46%) |

| Socioeconomic status (Annual income)* | |

|

$0.00-$19,999 $20,000-$39,999 $40,000-$59,999 $60,000-$79,999 $80,000-$99,999 $100,000-$149,999 $150,000 and over I prefer not to answer this question |

112 (9%) 227 (18%) 195 (16%) 169 (14%) 120 (10%) 157 (13%) 87 (7%) 71 (6%) |

| *Percentages do not add to 100% due to missing values and/or round off. | |

| Types of arthritis Survey respondents were diagnosed with | |

|

Osteoarthritis Rheumatoid arthritis Ankylosing spondylitis Psoriatic arthritis Fibromyalgia Gout Adult-onset Still’s disease Juvenile idiopathic arthritis Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (not visible on X-ray) Lupus Polymyalgia rheumatica Scleroderma Sjögrens syndrome Vasculitis Do not know Other |

18% 15% 14% 5% 4% 3% 2% 2% 2% 1% 1% 1% 1% 1% 26% 5% |

Listening to you

We hope you find this information of use. Please tell us what you think by writing to us or emailing us at feedback@jointhealth.org. Through your ongoing and active participation, ACE can make its work more relevant to all Canadians living with arthritis.

Update your email or postal address

Please let us know of any changes by contacting ACE at feedback@jointhealth.org. This will ensure that you continue to receive your free email or print copy of JointHealth™ insight.

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE)

Who We Are

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) and its team members acknowledge that they gather and work on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Coast Salish peoples -ʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) operates as a non-profit and provides free research based education and information to Canadians with arthritis. We help (em)power people living with all forms of arthritis to take control of their disease and to take action in healthcare and research decision making. ACE activities are guided by its members and led by people with arthritis, scientific and medical experts on the ACE Advisory Board. To learn more about ACE, visit www.jointhealth.org

Disclosures

Over the past 12 months, ACE received grants-in-aid from: Arthritis Research Canada, Amgen Canada, Canadian Biosimilars Forum, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canadian Rheumatology Association, Eli Lilly Canada, Fresenius Kabi Canada, Novartis Canada, Organon Canada, Pfizer Canada, Sandoz Canada, Teva Canada, UCB Canada, and the University of British Columbia.

ACE also received unsolicited donations from its community members (people with arthritis) across Canada.

ACE thanks funders for their support to help the nearly 6 million Canadians living with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and the many other forms of the disease.

Disclaimer

The material contained on this website is provided for general information only. This website should not be relied on to suggest a course of treatment for a particular individual or as a substitute for consultation with qualified health professionals who are familiar with your individual medical needs. Should you have any healthcare related questions, you should contact your physician. You should never disregard medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this or any website.

This site may provide links to other Internet sites only for the convenience of World Wide Web users. ACE is not responsible for the availability or content of these external sites, nor does ACE endorse, warrant or guarantee the products, services or information described or offered at these other Internet sites.

Although the information presented on this website is believed to be accurate at the time it is posted, this website could include inaccuracies, typographical errors or out-of-date information. This website may be changed at any time without prior notice.