In this issue

- RA: The evolution of treatment

- Today's Gold Standard of treatment for RA

- Research makes the difference

JointHealth™ insight February 2012

Inflammatory, or autoimmune, arthritis is a type of disease where the immune system attacks healthy joints and tissues, causing inflammation and joint damage. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common type. One of the rarest forms is called scleroderma.

Approximately 300,000 or 1 in 100 Canadians get RA. The disease causes inflammation (swelling and pain) in and around joints and can affect organs, including the eyes, lungs, and heart. Rheumatoid arthritis typically affects the hands and feet. The elbows, shoulders, neck, jaw, ankles, knees, and hips can also be affected. Over time, the damage to the bones and cartilage of the joints may lead to deformities. When moderate to severe, the disease takes as many as a dozen years off a person’s life.

Scleroderma affects approximately one in 2000 people. It is a complex and incurable disease of the immune system, blood vessels, and connective tissue. The symptoms include thickening of the skin. It can affect joints and internal organs and sometimes leads to disability.

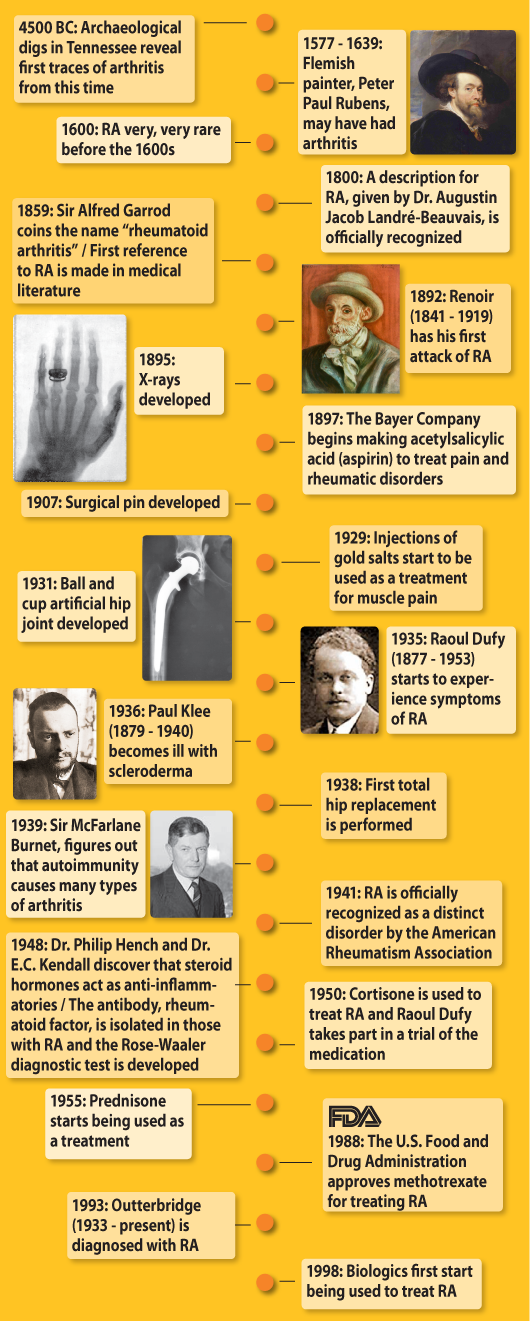

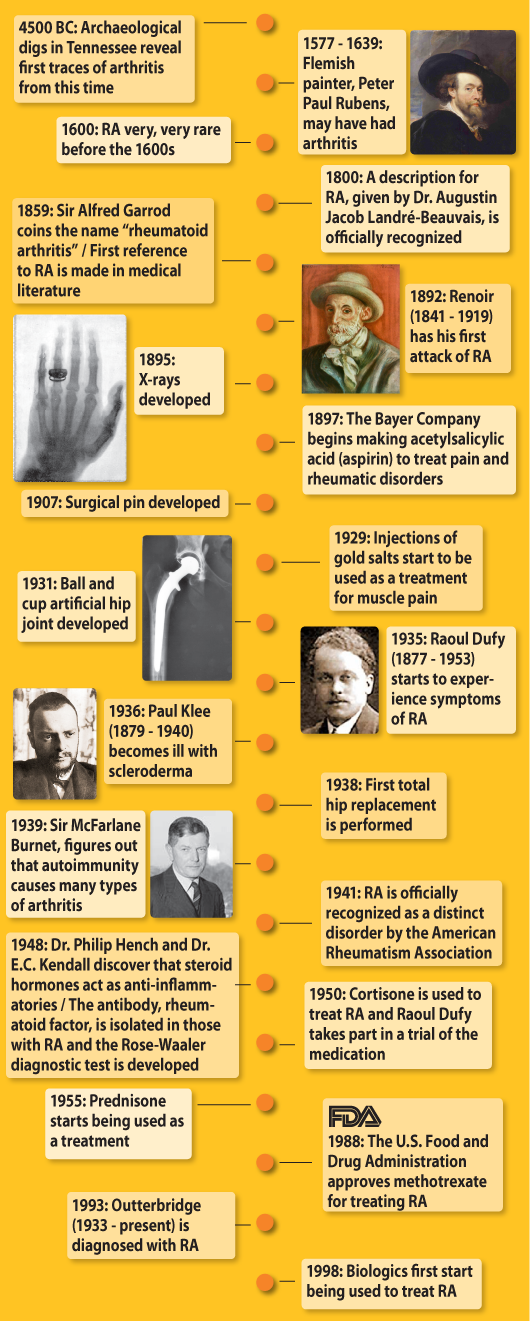

RA: The evolution of treatment

The cause of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is not yet known, but treatment for it has changed over the years as more has been learned about the disease. By looking to successful and famous personalities who lived with arthritis and whose achievements were influenced by RA, we can get a picture of the evolution of treatment.

We are following the example of some rheumatologists who used art to help them figure out how far back in history arthritis appears. One theory established from their research is that arthritis was very rare in Europe before the 1800s because it was not depicted in art before then.

Similarly, we are taking a historical look at artists who lived with arthritis. The artists discussed in this issue of JointHealth™ monthly are high achievers in a field that requires great manual dexterity. In spite of their disease, they continued to create art and they did so by sheer determination and by taking advantage of the resources and treatments of their time.

Experts have cited famous artists such as Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1639), Pierre Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) and Raoul Dufy (1877-1953) who were afflicted with rheumatoid arthritis and Paul Klee (1879-1940) who had scleroderma.

Studies of Flemish portraiture have concluded that Rubens had RA based on his depictions of swollen and deformed joints of the hands in his self-portraits. Furthermore, there are documents stating that Rubens complained of gout. In that period through to the nineteenth century, rheumatic conditions were often called gout.

Impressionist painter, Pierre Auguste Renoir had his first attack of arthritis in 1892. Renoir tried the only treatments available to him, namely moving to a warmer climate and spending time at the spa. Though Renoir lived in pain, he continued to paint even as his hands became disabled by the disease. By the time he died in 1919 at the age of 78, he had completed around 6,000 paintings.

French Fauvist painter, Raoul Dufy developed rheumatoid arthritis in 1935. He too, continued to paint as the disease progressed. In 1950 he travelled to Boston to take part in a clinical trial of cortisone. The treatment was successful and Dufy recovered the use of his hands and was able to paint the way he once had. Unfortunately, it was not long after he started treatment that he died from gastrointestinal bleeding, a possible side effect of the medication.

In 1936, avant-garde artist Paul Klee developed severe scleroderma, which changed the way he painted and limited his productivity. Klee lived with scleroderma for four years before he died, but it was not until ten years after his death that the illness was recognized in him. Even now, it is a hard disease to diagnose because symptoms differ widely among individuals. There is no cure, but scleroderma can be treated if it is diagnosed early. To read more about this rare disease, please read the JointHealth™ “Spotlight on scleroderma” at www.jointhealth.org.

John Outterbridge, a modern example, is an African American artist, community activist, and arts teacher. In 1993, at the age of 60, Outterbridge was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. His experience was radically different from his predecessors. Six years after his diagnosis, he began taking an anti-TNF biologic. So, unlike for the artists that came before him, his disease is well managed, allowing him to be a prolific sculptor, without having to live with extreme pain and disability.

What we can learn

Each artist was seriously affected by arthritis but was determined to keep doing their art in spite of their disease. Though, in the past their options were limited, they took advantage of what was available and found ways to get around their disability.

The common theme through all their examples is their own personal will. Renoir persevered through his pain without any therapy. Renoir and other artists living with arthritis demonstrate that patients with RA can do many things but they just need the time to do it. Now, modern artists, like Outterbridge, are taking biologics, which are medications that treat the symptoms of disease by targeting the cells involved in causing the immune system to attack itself.

These days, if you have rheumatoid arthritis (or any other arthritis type) there are many resources available to you. For you to take full advantage of them, it is important to do the research, talk to your doctor, and be proactive with your health. The JointHealth™ website, www.jointhealth.org, can help get you started.

Today's Gold Standard of treatment for RA

Medications are a cornerstone of rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Today’s gold standard of treatment looks like this:

Step 1:

Because people with active, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis are at high risk for irreparable joint damage caused by the disease’s symptoms it is very important for them to closely follow their treatment regimen. The regimen helps to prevent or reduce joint damage and disability and delivers the highest quality of life possible.

Exercise is also an important part of a successful treatment plan for rheumatoid arthritis. Appropriate stretching and strengthening of muscles and tendons surrounding affected joints can help to keep them stronger and healthier and is effective at reducing pain and maintaining mobility. Also, moderate forms of aerobic exercise can help to maintain a healthy body weight and lessen strain on joints. Swimming, walking, and cycling are often recommended but they must be done at a level that safely challenges a person’s aerobic capacity. A physiotherapist trained in rheumatoid arthritis is the ideal person to recommend a safe and effective exercise program.

Heat and cold can be used to decrease pain and stiffness. Hot showers can often relax aching muscles and reduce pain. Applying cold compresses, like ice packs, to swollen joints can help to reduce heat, pain and inflammation and allow a person to exercise more freely, or to recover from exercise more quickly.

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle is also critical in any arthritis treatment plan. A nutritionally sound diet that includes appropriate levels of calcium, vitamin D and folic acid is important. Managing stress levels, getting enough rest, and taking time to relax lead to a higher quality of life.

Research makes the difference

This brief history of arthritis demonstrates the importance of research. Dramatic advances in research over the past few decades have led to better treatments and hope for the future. Without the advances that have been made over the years, Outterbridge would be living in more pain, with a disability that would slow him down, and illness that would shorten his life.

Canada is a global leader in arthritis research. Sustained research efforts account for why people living with arthritis now have many treatment options, including surgery and medications, to manage their condition.

The research cannot end yet, however, because there is still no cure and treatments do not work for everyone; they can stop being effective and there can be side effects.

Continued research needs investment

Arthritis affects 16% of the Canadian population – more adults than diabetes, cancer, heart disease, asthma or spinal cord trauma – but receives much less research funding than other chronic diseases. The Canadian Institute of Health Research spent $19 million, a comparatively small sum, on arthritis research in 2005–2006. That is about $4.30 for every person living with arthritis in Canada, significantly less than many other diseases.

More funding for arthritis research is critical if we are to better understand how to prevent, treat and find a cure for the more than 100 different types of arthritis.

Listening to you

We hope you find this information of use. Please tell us what you think by writing to us or emailing us at info@jointhealth.org. Through your ongoing and active participation, ACE can make its work more relevant to all Canadians living with arthritis.

Update your email or postal address

Please let us know of any changes by contacting ACE at info@jointhealth.org. This will ensure that you continue to receive your free email or print copy of JointHealth™ monthly.

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE)

Who We Are

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) provides research-based education, advocacy training, advocacy leadership and information to Canadians with arthritis. We help empower people living with all forms of arthritis to take control of their disease and to take action in healthcare and research decision making. ACE activities are guided by its members and led by people with arthritis, leading medical professionals and the ACE Advisory Board. To learn more about ACE, visit: www.jointhealth.org

Acknowledgements

Over the past 12 months, ACE received unrestricted grants-in-aid from: Abbott Laboratories Ltd., Amgen Canada, Arthritis Research Centre of Canada, AstraZeneca Canada, Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffman-La Roche Canada Ltd., Merck & Co. Canada, Novartis Canada, Pfizer Canada, Sanofi-aventis Canada Inc., Takeda Canada, Inc., and UCB Canada Inc. ACE also receives unsolicited donations from its community members (people with arthritis) across Canada.

ACE thanks these private and public organizations and individuals.

Disclaimer

The material contained on this website is provided for general information only. This website should not be relied on to suggest a course of treatment for a particular individual or as a substitute for consultation with qualified health professionals who are familiar with your individual medical needs. Should you have any healthcare related questions, you should contact your physician. You should never disregard medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this or any website.

This site may provide links to other Internet sites only for the convenience of World Wide Web users. ACE is not responsible for the availability or content of these external sites, nor does ACE endorse, warrant or guarantee the products, services or information described or offered at these other Internet sites.

Although the information presented on this website is believed to be accurate at the time it is posted, this website could include inaccuracies, typographical errors or out-of-date information. This website may be changed at any time without prior notice.

Inflammatory, or autoimmune, arthritis is a type of disease where the immune system attacks healthy joints and tissues, causing inflammation and joint damage. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common type. One of the rarest forms is called scleroderma.

Approximately 300,000 or 1 in 100 Canadians get RA. The disease causes inflammation (swelling and pain) in and around joints and can affect organs, including the eyes, lungs, and heart. Rheumatoid arthritis typically affects the hands and feet. The elbows, shoulders, neck, jaw, ankles, knees, and hips can also be affected. Over time, the damage to the bones and cartilage of the joints may lead to deformities. When moderate to severe, the disease takes as many as a dozen years off a person’s life.

Scleroderma affects approximately one in 2000 people. It is a complex and incurable disease of the immune system, blood vessels, and connective tissue. The symptoms include thickening of the skin. It can affect joints and internal organs and sometimes leads to disability.

RA: The evolution of treatment

The cause of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is not yet known, but treatment for it has changed over the years as more has been learned about the disease. By looking to successful and famous personalities who lived with arthritis and whose achievements were influenced by RA, we can get a picture of the evolution of treatment.

We are following the example of some rheumatologists who used art to help them figure out how far back in history arthritis appears. One theory established from their research is that arthritis was very rare in Europe before the 1800s because it was not depicted in art before then.

Similarly, we are taking a historical look at artists who lived with arthritis. The artists discussed in this issue of JointHealth™ monthly are high achievers in a field that requires great manual dexterity. In spite of their disease, they continued to create art and they did so by sheer determination and by taking advantage of the resources and treatments of their time.

Experts have cited famous artists such as Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1639), Pierre Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) and Raoul Dufy (1877-1953) who were afflicted with rheumatoid arthritis and Paul Klee (1879-1940) who had scleroderma.

Studies of Flemish portraiture have concluded that Rubens had RA based on his depictions of swollen and deformed joints of the hands in his self-portraits. Furthermore, there are documents stating that Rubens complained of gout. In that period through to the nineteenth century, rheumatic conditions were often called gout.

Impressionist painter, Pierre Auguste Renoir had his first attack of arthritis in 1892. Renoir tried the only treatments available to him, namely moving to a warmer climate and spending time at the spa. Though Renoir lived in pain, he continued to paint even as his hands became disabled by the disease. By the time he died in 1919 at the age of 78, he had completed around 6,000 paintings.

French Fauvist painter, Raoul Dufy developed rheumatoid arthritis in 1935. He too, continued to paint as the disease progressed. In 1950 he travelled to Boston to take part in a clinical trial of cortisone. The treatment was successful and Dufy recovered the use of his hands and was able to paint the way he once had. Unfortunately, it was not long after he started treatment that he died from gastrointestinal bleeding, a possible side effect of the medication.

In 1936, avant-garde artist Paul Klee developed severe scleroderma, which changed the way he painted and limited his productivity. Klee lived with scleroderma for four years before he died, but it was not until ten years after his death that the illness was recognized in him. Even now, it is a hard disease to diagnose because symptoms differ widely among individuals. There is no cure, but scleroderma can be treated if it is diagnosed early. To read more about this rare disease, please read the JointHealth™ “Spotlight on scleroderma” at www.jointhealth.org.

John Outterbridge, a modern example, is an African American artist, community activist, and arts teacher. In 1993, at the age of 60, Outterbridge was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. His experience was radically different from his predecessors. Six years after his diagnosis, he began taking an anti-TNF biologic. So, unlike for the artists that came before him, his disease is well managed, allowing him to be a prolific sculptor, without having to live with extreme pain and disability.

What we can learn

Each artist was seriously affected by arthritis but was determined to keep doing their art in spite of their disease. Though, in the past their options were limited, they took advantage of what was available and found ways to get around their disability.

The common theme through all their examples is their own personal will. Renoir persevered through his pain without any therapy. Renoir and other artists living with arthritis demonstrate that patients with RA can do many things but they just need the time to do it. Now, modern artists, like Outterbridge, are taking biologics, which are medications that treat the symptoms of disease by targeting the cells involved in causing the immune system to attack itself.

These days, if you have rheumatoid arthritis (or any other arthritis type) there are many resources available to you. For you to take full advantage of them, it is important to do the research, talk to your doctor, and be proactive with your health. The JointHealth™ website, www.jointhealth.org, can help get you started.

Today's Gold Standard of treatment for RA

Medications are a cornerstone of rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Today’s gold standard of treatment looks like this:

Step 1:

- A person newly diagnosed with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis is typically started on methotrexate, and possibly one or two other DMARDs in combination with methotrexate, such as sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine (this is called triple therapy). While waiting for the medications to take effect, an NSAID or cox-2 inhibitor or in some cases prednisone, can be used to reduce inflammation quickly.

- For those who do not respond, or do not respond well enough, to the combination therapy (that is, their inflammation is not well controlled), then they would be considered a good candidate for a biologic response modifier (biologic) medication. Only one is used at any given time. Biologics are usually used in combination with methotrexate.

Because people with active, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis are at high risk for irreparable joint damage caused by the disease’s symptoms it is very important for them to closely follow their treatment regimen. The regimen helps to prevent or reduce joint damage and disability and delivers the highest quality of life possible.

Exercise is also an important part of a successful treatment plan for rheumatoid arthritis. Appropriate stretching and strengthening of muscles and tendons surrounding affected joints can help to keep them stronger and healthier and is effective at reducing pain and maintaining mobility. Also, moderate forms of aerobic exercise can help to maintain a healthy body weight and lessen strain on joints. Swimming, walking, and cycling are often recommended but they must be done at a level that safely challenges a person’s aerobic capacity. A physiotherapist trained in rheumatoid arthritis is the ideal person to recommend a safe and effective exercise program.

Heat and cold can be used to decrease pain and stiffness. Hot showers can often relax aching muscles and reduce pain. Applying cold compresses, like ice packs, to swollen joints can help to reduce heat, pain and inflammation and allow a person to exercise more freely, or to recover from exercise more quickly.

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle is also critical in any arthritis treatment plan. A nutritionally sound diet that includes appropriate levels of calcium, vitamin D and folic acid is important. Managing stress levels, getting enough rest, and taking time to relax lead to a higher quality of life.

Research makes the difference

This brief history of arthritis demonstrates the importance of research. Dramatic advances in research over the past few decades have led to better treatments and hope for the future. Without the advances that have been made over the years, Outterbridge would be living in more pain, with a disability that would slow him down, and illness that would shorten his life.

Canada is a global leader in arthritis research. Sustained research efforts account for why people living with arthritis now have many treatment options, including surgery and medications, to manage their condition.

The research cannot end yet, however, because there is still no cure and treatments do not work for everyone; they can stop being effective and there can be side effects.

Continued research needs investment

Arthritis affects 16% of the Canadian population – more adults than diabetes, cancer, heart disease, asthma or spinal cord trauma – but receives much less research funding than other chronic diseases. The Canadian Institute of Health Research spent $19 million, a comparatively small sum, on arthritis research in 2005–2006. That is about $4.30 for every person living with arthritis in Canada, significantly less than many other diseases.

More funding for arthritis research is critical if we are to better understand how to prevent, treat and find a cure for the more than 100 different types of arthritis.

Listening to you

We hope you find this information of use. Please tell us what you think by writing to us or emailing us at info@jointhealth.org. Through your ongoing and active participation, ACE can make its work more relevant to all Canadians living with arthritis.

Update your email or postal address

Please let us know of any changes by contacting ACE at info@jointhealth.org. This will ensure that you continue to receive your free email or print copy of JointHealth™ monthly.

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE)

Who We Are

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) provides research-based education, advocacy training, advocacy leadership and information to Canadians with arthritis. We help empower people living with all forms of arthritis to take control of their disease and to take action in healthcare and research decision making. ACE activities are guided by its members and led by people with arthritis, leading medical professionals and the ACE Advisory Board. To learn more about ACE, visit: www.jointhealth.org

Acknowledgements

Over the past 12 months, ACE received unrestricted grants-in-aid from: Abbott Laboratories Ltd., Amgen Canada, Arthritis Research Centre of Canada, AstraZeneca Canada, Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffman-La Roche Canada Ltd., Merck & Co. Canada, Novartis Canada, Pfizer Canada, Sanofi-aventis Canada Inc., Takeda Canada, Inc., and UCB Canada Inc. ACE also receives unsolicited donations from its community members (people with arthritis) across Canada.

ACE thanks these private and public organizations and individuals.

Disclaimer

The material contained on this website is provided for general information only. This website should not be relied on to suggest a course of treatment for a particular individual or as a substitute for consultation with qualified health professionals who are familiar with your individual medical needs. Should you have any healthcare related questions, you should contact your physician. You should never disregard medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this or any website.

This site may provide links to other Internet sites only for the convenience of World Wide Web users. ACE is not responsible for the availability or content of these external sites, nor does ACE endorse, warrant or guarantee the products, services or information described or offered at these other Internet sites.

Although the information presented on this website is believed to be accurate at the time it is posted, this website could include inaccuracies, typographical errors or out-of-date information. This website may be changed at any time without prior notice.