In this issue

- A note on the underrepresentation of Black, Indigenous and people of colour

- Access to arthritis specific virtual healthcare services

- Satisfaction with virtual care services

- Discussion

- References

JointHealth™ insight Published May 2021

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) led a national survey, in English and French, from January to February 2021. The aim of the survey was to understand the arthritis patient community’s experiences using virtual care services as well as their preferences on how virtual care services are delivered. ACE recently published a summary of respondent’s answers to the survey questions, including general high-level findings. This current article is a deeper look at the findings specific to health inequities.

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) led a national survey, in English and French, from January to February 2021. The aim of the survey was to understand the arthritis patient community’s experiences using virtual care services as well as their preferences on how virtual care services are delivered. ACE recently published a summary of respondent’s answers to the survey questions, including general high-level findings. This current article is a deeper look at the findings specific to health inequities.

A note on the underrepresentation of Black, Indigenous and people of colour

A key goal of the survey was to understand how access to virtual care services, and experiences using virtual care services, differ among various groups in the arthritis patient community. In other words, to identify differences in respondents’ experiences using virtual care services that are unjust. Although the survey had responses from across different age groups, disease areas, genders and urban/rural locations, there was not equal representation across racial groups. This is to say that white respondents were overrepresented, and non-white respondents were significantly underrepresented. More specifically, only 5.5% of respondents identified as Black, Indigenous, or a person of colour (BIPOC). When it came to the French version of the survey, there were no BIPOC respondents.

This major underrepresentation of BIPOC respondents is a very important finding in and of itself. It suggests that racial minorities are generally being excluded from networks in the arthritis patient community. This means the voices and experiences of BIPOC people living with arthritis are largely going unheard. This is a particularly significant problem due to the fact that BIPOC people are actually more likely to experience negative health outcomes (due to systemic racism) in a number of disease areas, including arthritis. Patient organizations, including ACE, must do a better job of reaching these communities.

The small percentage of BIPOC respondents also means that there are certain limitations to our survey findings, including those related to racial inequalities. There is not a large enough number of BIPOC respondents for us to generalize the findings (to apply the findings to the patient community at large). However, with this being said, we have observed some very interesting patterns which are still considered ‘statistically significant’, even with the small number of BIPOC respondents. These findings are incredibly important. We hope that you will take the time to read them over, reflect on them, and consider sharing them with members of your network.

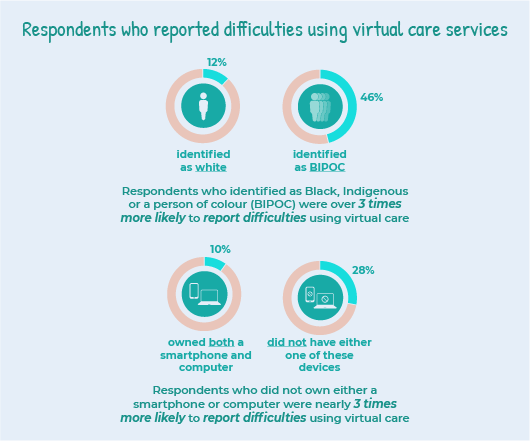

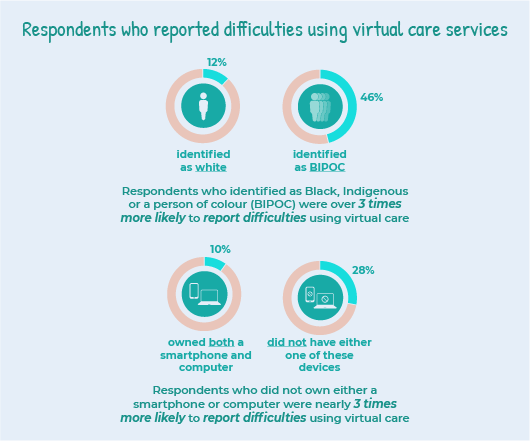

Respondents who reported difficulties using virtual care services

In the survey, we asked respondents if any factors have made it difficult for them to use virtual care services. They could select multiple answers from a list of options. The options included:

There was also a strong relationship between difficulties using virtual care and whether or not respondents owned a smart phone and computer. In other words, if a respondent owned both a smartphone and computer, they had a fairly low likelihood of reporting any difficulties (10%). In contrast, if a respondent lacked either one of these devices, their likelihood of facing difficulties was nearly 3 times higher (28%).

The most common difficulty that respondents reported facing was “I don’t feel comfortable or know how to use the virtual care technology being used by my health care professional”. Importantly, we found that there were a number of different groups that were more likely to experience this issue, including:

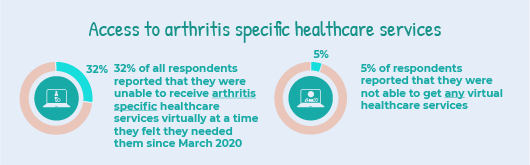

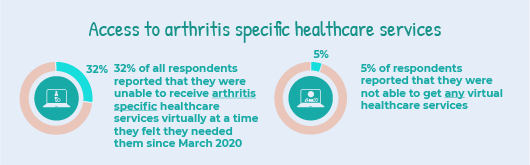

Access to arthritis specific virtual healthcare services

Getting access to virtual care services in a timely manner appears to be a significant issue for the arthritis patient community in general. In fact, 32 per cent of all respondents reported that they were unable to receive arthritis specific healthcare services virtually at a time they felt they needed them since March 2020. Five per cent of respondents reported that they were not able to get any virtual healthcare services.

Our findings showed that respondents who identified as BIPOC were more likely to be in the group that were unable to get any virtual healthcare services. This suggests that while timeliness of care is an issue for respondents in general, getting any access to care at all may be the bigger issue for BIPOC living with arthritis. However, it is important to note that this relationship was not as strong as others discussed in this report. It is considered a “borderline statistically significant finding”. Therefore, we cannot draw any firm conclusions from it, but it is an important topic to explore in future research.

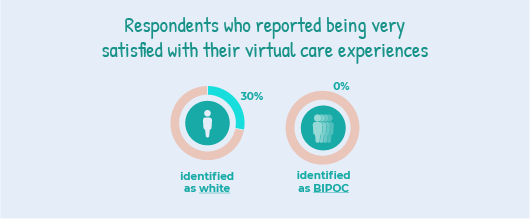

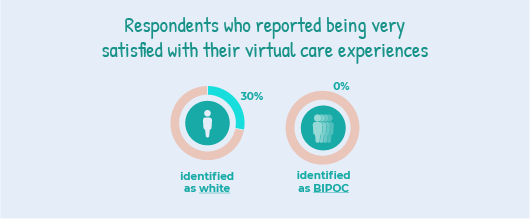

Satisfaction with virtual care services

In the survey, we asked respondents if they were satisfied sharing their concerns and getting advice from healthcare providers through virtual care services. They selected an answer on a scale from ‘very dissatisfied’ to ‘very satisfied’. In general, satisfaction is related to respondents’ emotions, feelings and perceptions regarding healthcare services. This is an important measure because researchers often consider satisfaction to be a substitute for the quality of care a patient is receiving. It has also been shown to have a direct impact on health outcomes1.

The survey results showed that satisfaction with virtual care services was strongly tied to race.

Those who did not self-identify as BIPOC were much more likely to be very satisfied with their virtual care experiences than those who identified as BIPOC. More specifically, 30% of white respondents selected that they were very satisfied, compared to 0% of BIPOC respondents. In general, the satisfaction levels of white respondents were also more spread out, although this is likely due to having a higher number of white respondents compared to BIPOC respondents.

Past research suggests that racial minorities – particularly Indigenous peoples in Canada – commonly experience discrimination in healthcare settings2,3. It is possible that BIPOC respondents are less likely to be very satisfied with virtual care services due to such experiences. Therefore, these survey findings may be representing BIPOC respondents’ satisfaction with healthcare in general, rather than specifically being in relation to satisfaction with virtual care services.

Discussion

Discussion

Although there are limitations to our survey findings, we uncovered some very concerning patterns that suggest Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC) living with arthritis are facing substantial inequities when it comes to virtual care.

Respondents living with arthritis who identified as Black, Indigenous or a person of colour were:

These findings are supported by scientific research that suggests BIPOC people frequently experience lower access to healthcare and lower quality of healthcare in general. This can be understood as a symptom of systemic racism within the healthcare system2,3.

We also found that respondents who did not own both a smart phone and computer were 3 times more likely to experience factors that made it difficult to use virtual care services. This was a ‘highly statistically significant’ finding.

It is possible that the ownership of electronic devices may represent the income level of respondents. If this is the case, then our findings suggest that there are significant inequities related to both race and income when it comes to respondents’ access to virtual healthcare services.

Virtual care services offer exciting possibilities for the future of arthritis specific healthcare services; however, if care is not taken in policy development, certain patient groups will fall through the cracks.

Overall, findings from the “ACE National Survey on Virtual Care Services for People Living with Arthritis” point to the urgent need for partnerships with those communities most impacted by health inequities - largely patients who are Black, Indigenous or people of colour. BIPOC are currently not being adequately represented in the arthritis patient community, and no meaningful changes can be made until this significant issue is addressed.

ACE is committed to forming meaningful partnerships with members of the BIPOC community to ensure that all arthritis patient voices are being heard and amplified in our advocacy efforts. We are actively reaching out to organizations that represent BIPOC community members affected to find ways to support them in their effort to provide arthritis information, education and advocacy to their community members.

Want to learn more about health inequities in arthritis? Please take time to read our special series on the topic and consider sharing it with other people in your network.

Acknowledgment

ACE extends its sincere thanks to Eric Sayre and Adriana Lima from Arthritis Research Canada who provided statistical analysis and interpretation of the data for this project.

References

Listening to you

We hope you find this information of use. Please tell us what you think by writing to us or emailing us at feedback@jointhealth.org. Through your ongoing and active participation, ACE can make its work more relevant to all Canadians living with arthritis.

Update your email or postal address

Please let us know of any changes by contacting ACE at feedback@jointhealth.org. This will ensure that you continue to receive your free email or print copy of JointHealth™ insight.

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE)

Who We Are

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) operates as a non-profit and provides free research based education and information to Canadians with arthritis. We help (em)power people living with all forms of arthritis to take control of their disease and to take action in healthcare and research decision making. ACE activities are guided by its members and led by people with arthritis, scientific and medical experts on the ACE Advisory Board. To learn more about ACE, visit www.jointhealth.org

Disclosures

Over the past 12 months, ACE received grants-in-aid from: Arthritis Research Canada, Amgen Canada, Canadian Biosimilars Forum, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canadian Rheumatology Association, Eli Lilly Canada, Fresenius Kabi Canada, Gilead Sciences Canada, Hoffman-La Roche Canada Ltd., Knowledge Translation Canada, Merck Canada, Novartis Canada, Pfizer Canada, Sandoz Canada, Sanofi Canada, St. Paul's Hospital (Vancouver), Teva Canada, UCB Canada, and the University of British Columbia.

ACE also received unsolicited donations from its community members (people with arthritis) across Canada.

ACE thanks funders for their support to help the nearly 6 million Canadians living with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and the many other forms of the disease.

Disclaimer

The material contained on this website is provided for general information only. This website should not be relied on to suggest a course of treatment for a particular individual or as a substitute for consultation with qualified health professionals who are familiar with your individual medical needs. Should you have any healthcare related questions, you should contact your physician. You should never disregard medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this or any website.

This site may provide links to other Internet sites only for the convenience of World Wide Web users. ACE is not responsible for the availability or content of these external sites, nor does ACE endorse, warrant or guarantee the products, services or information described or offered at these other Internet sites.

Although the information presented on this website is believed to be accurate at the time it is posted, this website could include inaccuracies, typographical errors or out-of-date information. This website may be changed at any time without prior notice.

A note on the underrepresentation of Black, Indigenous and people of colour

A key goal of the survey was to understand how access to virtual care services, and experiences using virtual care services, differ among various groups in the arthritis patient community. In other words, to identify differences in respondents’ experiences using virtual care services that are unjust. Although the survey had responses from across different age groups, disease areas, genders and urban/rural locations, there was not equal representation across racial groups. This is to say that white respondents were overrepresented, and non-white respondents were significantly underrepresented. More specifically, only 5.5% of respondents identified as Black, Indigenous, or a person of colour (BIPOC). When it came to the French version of the survey, there were no BIPOC respondents.

This major underrepresentation of BIPOC respondents is a very important finding in and of itself. It suggests that racial minorities are generally being excluded from networks in the arthritis patient community. This means the voices and experiences of BIPOC people living with arthritis are largely going unheard. This is a particularly significant problem due to the fact that BIPOC people are actually more likely to experience negative health outcomes (due to systemic racism) in a number of disease areas, including arthritis. Patient organizations, including ACE, must do a better job of reaching these communities.

| Did you know that Black, Indigenous and people of colour are often underrepresented in health research in general, including clinical trials for arthritis treatment? Learn more about this topic in our health inequities article, ‘Who is and who is not represented in research?’. |

Respondents who reported difficulties using virtual care services

In the survey, we asked respondents if any factors have made it difficult for them to use virtual care services. They could select multiple answers from a list of options. The options included:

- access to the internet

- cost of electronics

- the language that virtual care is offered in (e.g., lack of translation services)

- I don’t feel comfortable or know how to use the virtual care technology being used by my health care professional

- I do not have any issues using virtual care services

There was also a strong relationship between difficulties using virtual care and whether or not respondents owned a smart phone and computer. In other words, if a respondent owned both a smartphone and computer, they had a fairly low likelihood of reporting any difficulties (10%). In contrast, if a respondent lacked either one of these devices, their likelihood of facing difficulties was nearly 3 times higher (28%).

The most common difficulty that respondents reported facing was “I don’t feel comfortable or know how to use the virtual care technology being used by my health care professional”. Importantly, we found that there were a number of different groups that were more likely to experience this issue, including:

- respondents who were older;

- respondents who do not own both a smartphone and computer; and,

- respondents who identified as BIPOC. This relationship between discomfort and race was the strongest, where 39% of BIPOC respondents reported facing this issue, compared to just under 7% of white respondents.

Access to arthritis specific virtual healthcare services

Getting access to virtual care services in a timely manner appears to be a significant issue for the arthritis patient community in general. In fact, 32 per cent of all respondents reported that they were unable to receive arthritis specific healthcare services virtually at a time they felt they needed them since March 2020. Five per cent of respondents reported that they were not able to get any virtual healthcare services.

Our findings showed that respondents who identified as BIPOC were more likely to be in the group that were unable to get any virtual healthcare services. This suggests that while timeliness of care is an issue for respondents in general, getting any access to care at all may be the bigger issue for BIPOC living with arthritis. However, it is important to note that this relationship was not as strong as others discussed in this report. It is considered a “borderline statistically significant finding”. Therefore, we cannot draw any firm conclusions from it, but it is an important topic to explore in future research.

Satisfaction with virtual care services

In the survey, we asked respondents if they were satisfied sharing their concerns and getting advice from healthcare providers through virtual care services. They selected an answer on a scale from ‘very dissatisfied’ to ‘very satisfied’. In general, satisfaction is related to respondents’ emotions, feelings and perceptions regarding healthcare services. This is an important measure because researchers often consider satisfaction to be a substitute for the quality of care a patient is receiving. It has also been shown to have a direct impact on health outcomes1.

The survey results showed that satisfaction with virtual care services was strongly tied to race.

Those who did not self-identify as BIPOC were much more likely to be very satisfied with their virtual care experiences than those who identified as BIPOC. More specifically, 30% of white respondents selected that they were very satisfied, compared to 0% of BIPOC respondents. In general, the satisfaction levels of white respondents were also more spread out, although this is likely due to having a higher number of white respondents compared to BIPOC respondents.

Past research suggests that racial minorities – particularly Indigenous peoples in Canada – commonly experience discrimination in healthcare settings2,3. It is possible that BIPOC respondents are less likely to be very satisfied with virtual care services due to such experiences. Therefore, these survey findings may be representing BIPOC respondents’ satisfaction with healthcare in general, rather than specifically being in relation to satisfaction with virtual care services.

Discussion

DiscussionAlthough there are limitations to our survey findings, we uncovered some very concerning patterns that suggest Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC) living with arthritis are facing substantial inequities when it comes to virtual care.

Respondents living with arthritis who identified as Black, Indigenous or a person of colour were:

- significantly more likely to experience factors that made it difficult to use virtual care services (highly statistically significant finding);

- more likely to report having no access to virtual care services (borderline statistically significant finding); and,

- less likely to be very satisfied with their virtual care experiences (highly statistically significant finding).

|

What is statistical significance? “Statistical significance” refers to a mathematical technique to measure whether the results of a study are likely to be “real”, or simply caused by chance (such as the relationship between race and access to virtual care). When a finding is likely not caused by chance, it is considered statistically significant. |

We also found that respondents who did not own both a smart phone and computer were 3 times more likely to experience factors that made it difficult to use virtual care services. This was a ‘highly statistically significant’ finding.

It is possible that the ownership of electronic devices may represent the income level of respondents. If this is the case, then our findings suggest that there are significant inequities related to both race and income when it comes to respondents’ access to virtual healthcare services.

|

An important note about these survey results: Because our survey was conducted online, and respondents needed internet access in order to complete it, it did not include the experiences of those who do not have internet access, which, of course, is a major barrier to accessing virtual care services. Existing research suggests that 55% of rural and remote Canadian households do not have basic internet access as defined by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission4. The rate is even higher for rural and remote Indigenous communities5. Importantly, it is patients in these regions who may benefit the most from virtual care services due to a lack of in-person arthritis specific healthcare services in rural and remote areas. Therefore, for the benefits of virtual care services to be equitably distributed, governments in Canada must take action to ensure access to the internet for all Canadians. Access to the internet was actually declared a human right by the United Nations in 20165. |

Overall, findings from the “ACE National Survey on Virtual Care Services for People Living with Arthritis” point to the urgent need for partnerships with those communities most impacted by health inequities - largely patients who are Black, Indigenous or people of colour. BIPOC are currently not being adequately represented in the arthritis patient community, and no meaningful changes can be made until this significant issue is addressed.

ACE is committed to forming meaningful partnerships with members of the BIPOC community to ensure that all arthritis patient voices are being heard and amplified in our advocacy efforts. We are actively reaching out to organizations that represent BIPOC community members affected to find ways to support them in their effort to provide arthritis information, education and advocacy to their community members.

Want to learn more about health inequities in arthritis? Please take time to read our special series on the topic and consider sharing it with other people in your network.

|

Are you a member in the Black, Indigenous and people of colour community and interested in addressing health inequities? Please email us at feedback@jointhealth.org for collaboration opportunities. |

Acknowledgment

ACE extends its sincere thanks to Eric Sayre and Adriana Lima from Arthritis Research Canada who provided statistical analysis and interpretation of the data for this project.

References

| 1 | Han, W., & Lee, S. (2016). Racial/ethnic variation in health care satisfaction: The role of acculturation. Social Work in Health Care, 55(9), 694–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2016.1191580 |

| 2 | Turpel-Lafond, M. E. (2020). In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-Specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care. [Independent Investigation]. Government of British Columbia. |

| 3 | Arthritis Consumer Experts JointHealth™ insight. (2020). Health inequities in arthritis: Structural racism affecting Indigenous Peoples’ Healthcare. Jointhealth.org. https://jointhealth.org/programs-jhinsight-view. cfm?id=1261&locale=en-CA |

| 4 | Government of Canada, C. R. and T. C. (CRTC). (2016, January 14). Broadband fund: Closing the digital divide in Canada [Consumer information]. https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/internet/internet.htm |

| 5 | Indigenous people seeking digital equity as BC enshrines UN Declaration into provincial law – First Nations Technology Council. (n.d.). Retrieved April 23, 2021, from https://technologycouncil.ca/2019/11/30/indigenous-people-seeking-digital-equity-as-bc-enshrines-un-declaration-into-provincial-law/ |

Listening to you

We hope you find this information of use. Please tell us what you think by writing to us or emailing us at feedback@jointhealth.org. Through your ongoing and active participation, ACE can make its work more relevant to all Canadians living with arthritis.

Update your email or postal address

Please let us know of any changes by contacting ACE at feedback@jointhealth.org. This will ensure that you continue to receive your free email or print copy of JointHealth™ insight.

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE)

Who We Are

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) operates as a non-profit and provides free research based education and information to Canadians with arthritis. We help (em)power people living with all forms of arthritis to take control of their disease and to take action in healthcare and research decision making. ACE activities are guided by its members and led by people with arthritis, scientific and medical experts on the ACE Advisory Board. To learn more about ACE, visit www.jointhealth.org

Disclosures

Over the past 12 months, ACE received grants-in-aid from: Arthritis Research Canada, Amgen Canada, Canadian Biosimilars Forum, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canadian Rheumatology Association, Eli Lilly Canada, Fresenius Kabi Canada, Gilead Sciences Canada, Hoffman-La Roche Canada Ltd., Knowledge Translation Canada, Merck Canada, Novartis Canada, Pfizer Canada, Sandoz Canada, Sanofi Canada, St. Paul's Hospital (Vancouver), Teva Canada, UCB Canada, and the University of British Columbia.

ACE also received unsolicited donations from its community members (people with arthritis) across Canada.

ACE thanks funders for their support to help the nearly 6 million Canadians living with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and the many other forms of the disease.

Disclaimer

The material contained on this website is provided for general information only. This website should not be relied on to suggest a course of treatment for a particular individual or as a substitute for consultation with qualified health professionals who are familiar with your individual medical needs. Should you have any healthcare related questions, you should contact your physician. You should never disregard medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this or any website.

This site may provide links to other Internet sites only for the convenience of World Wide Web users. ACE is not responsible for the availability or content of these external sites, nor does ACE endorse, warrant or guarantee the products, services or information described or offered at these other Internet sites.

Although the information presented on this website is believed to be accurate at the time it is posted, this website could include inaccuracies, typographical errors or out-of-date information. This website may be changed at any time without prior notice.