In this issue

- Structural issues impacting Indigenous health outcomes

- Gaps in health outcomes are not ‘by chance’

- Indigenous models of care

- A path forward

- COVID-19 mortality rates higher in visible minority communities

- Indigenous Communities & COVID-19

JointHealth™ insight Published Fall 2020

The past year of discontent and disruption has seen the world’s attention focused on racial health inequities and systemic racism brought under sharp relief by the pandemic and Black Lives Matter Movement. In Canada, many advocates and community leaders have added their voices to this conversation, sharing many examples of the systemic nature of racism contained within our healthcare system and focusing on the frequent racism Indigenous Peoples experience in Canadian healthcare. Most recently, Joyce Echaquan – Atikamekw woman and mother of 7 – recorded a Facebook live video of healthcare workers making racist and horrific comments towards her in the moments before she passed away. While this specific story made national and international headlines, similar experiences of racism have been recorded in hospitals across the country.

The health inequities faced by Indigenous Peoples in Canada is an important issue to understand in our arthritis community where Indigenous Peoples have some of the highest rates of serious or life–threatening arthritis in the world, are at greater risk for becoming disabled by arthritis and also face a high rate of co-morbidities like heart disease, hypertension, asthma and cancer.

In this issue of JointHealth™ insight, ACE, in collaboration with Graeme Reed, Chair of the Canadian Spondylitis Association’s Board of Directors, and a person of mixed Anishinaabe and European descent, examines elements of the structural racism impacting Indigenous health outcomes and highlights Indigenous models of care as essential tools to address these health inequities.

Listening to you

We hope you find this information of use. Please tell us what you think by writing to us or emailing us at feedback@jointhealth.org. Through your ongoing and active participation, ACE can make its work more relevant to all Canadians living with arthritis.

Update your email or postal address

Please let us know of any changes by contacting ACE at feedback@jointhealth.org. This will ensure that you continue to receive your free email or print copy of JointHealth™ insight.

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE)

Who We Are

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) operates as a non-profit and provides free research based education and information to Canadians with arthritis. We help (em)power people living with all forms of arthritis to take control of their disease and to take action in healthcare and research decision making. ACE activities are guided by its members and led by people with arthritis, scientific and medical experts on the ACE Advisory Board. To learn more about ACE, visit www.jointhealth.org

Disclosures

Over the past 12 months, ACE received grants- in-aid from: Arthritis Research Canada, Amgen Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canadian Rheumatology Association, Eli Lilly Canada, Hoffman-La Roche Canada Ltd., Knowledge Translation Canada, Merck Canada, Novartis Canada, Pfizer Canada, Sandoz Canada, Sanofi Canada, St. Paul’s Hospital (Vancouver), UCB Canada, and the University of British Columbia.

ACE also received unsolicited donations from its community members (people with arthritis) across Canada.

ACE thanks funders for their support to help the nearly 6 million Canadians living with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and the many other forms of the disease.

Disclaimer

The material contained on this website is provided for general information only. This website should not be relied on to suggest a course of treatment for a particular individual or as a substitute for consultation with qualified health professionals who are familiar with your individual medical needs. Should you have any healthcare related questions, you should contact your physician. You should never disregard medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this or any website.

This site may provide links to other Internet sites only for the convenience of World Wide Web users. ACE is not responsible for the availability or content of these external sites, nor does ACE endorse, warrant or guarantee the products, services or information described or offered at these other Internet sites.

Although the information presented on this website is believed to be accurate at the time it is posted, this website could include inaccuracies, typographical errors or out-of-date information. This website may be changed at any time without prior notice.

The health inequities faced by Indigenous Peoples in Canada is an important issue to understand in our arthritis community where Indigenous Peoples have some of the highest rates of serious or life–threatening arthritis in the world, are at greater risk for becoming disabled by arthritis and also face a high rate of co-morbidities like heart disease, hypertension, asthma and cancer.

In this issue of JointHealth™ insight, ACE, in collaboration with Graeme Reed, Chair of the Canadian Spondylitis Association’s Board of Directors, and a person of mixed Anishinaabe and European descent, examines elements of the structural racism impacting Indigenous health outcomes and highlights Indigenous models of care as essential tools to address these health inequities.

Structural issues impacting Indigenous health outcomes

There is a great diversity of Indigenous experiences within the healthcare system, especially between the realities of Inuit, Métis, and First Nations (both on-reserve and off-reserve). Despite this, Indigenous patients are often required to navigate multiple systems of care, whether federal, provincial, territorial, or Indigenous run.

The navigation of different health services for First Nations, both on- and off-reserve, whether federal, provincial, or band–run, often results in a complicated, patchwork system that inevitably result in certain individuals falling through the cracks, being forced to pay out of pocket for services guaranteed within Treaty or other constructive arrangements. For example, research has demonstrated healthcare professionals (HCPs) often do not know who pays for what1. This uncertainty has been most evident in the discussions around Jordan’s Principle – a principle that arose from the passing of 5-year-old Jordan River Anderson from Norway House Cree Nation when he did not receive proper care because the governments of Canada and Manitoba could not agree on who should pay for what services.Since this point, Jordan’s Principle has guaranteed that First Nations children receive the necessary care they need, when they need it, with payments worked out afterwards2. Jordan’s Principle has been extended to include Inuit children in the Inuit Child First Initiative.

In terms of access to medications, the non-insured health benefits (NIHB) program provides supplementary health benefits, including prescription and non-prescription drugs, for registered First Nations and recognized Inuit throughout Canada. In Northwest Territories, the NIHB is the only public drug plan3.

In an arthritis context, ACE’s Medications Report Card has shown that the NIHB is not equal to other provincial drug plans. Over the Report Card’s 12-year history, NIHB has consistently ranked at or near the lowest in terms of providing reimbursement for inflammatory arthritis medication.

Gaps in health outcomes are not ‘by chance’

Similar findings related to Indigenous health outcomes in other countries with a history of settler colonialism show us that these imbalanced outcomes are a symptom of a broader problem and violence against Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous Peoples in Aotearoa/New Zealand, the United States, Canada, and Australia all experience higher prevalence and severity of arthritis, higher rates of hospitalizations but fewer visits to specialists than the non-Indigenous population. More specifically, researchers from the University of Calgary found that Indigenous populations had up to 50% fewer visits to specialists than non-Indigenous populations (In Canada and Aotearoa/New Zealand), but up to 300% more hospitalizations due to arthritis complications (in Canada, Aotearoa/New Zealand and the United States6).

Indigenous models of care

In the development of a First Nations-centric perspective on healthcare, the Assembly of First Nations worked with Elders and Knowledge Keepers to propose a new path forward of health systems under the First Nations Health Transformation Agenda that reflect First Nations and their ways of life: “The Elders have a vision for First Nations health that reflects a wholistic understanding of health that includes physical, emotional, mental and spiritual wellness. This vision is grounded in our nationhood and guided by the sacred principles gifted to us by our ancestors and the Creator7.” This approach to healing is fundamentally different than what is traditionally conceived within ‘mainstream’ healthcare systems.

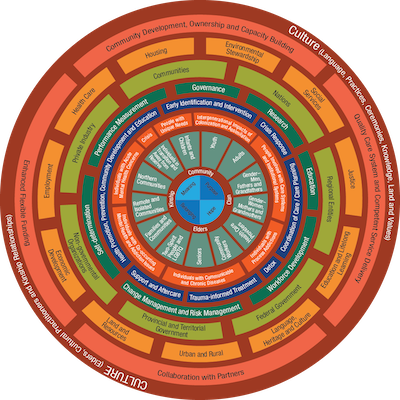

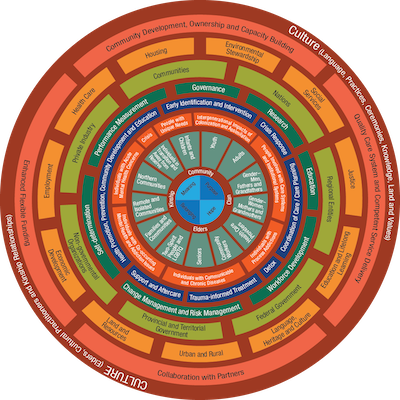

Source: https://thunderbirdpf.org/first-nations-mental-wellness-continuum-framework/

Source: https://thunderbirdpf.org/first-nations-mental-wellness-continuum-framework/

To demonstrate a wholistic approach to healing, above is a graphic representing the First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum. This comprehensive framework is rooted in the Indigenous social determinants of health, which emphasize First Nations culture as a crucial element to effective health programs and service delivery.

Unfortunately, this worldview is not well-understood or adopted in mainstream rheumatology practices. A recent survey of rheumatologists in Canada found that most respondents (73%) were unclear or unaware of what Indigenous healing practices were but nearly all respondents (93%) were open to the idea of including Indigenous healing practices in rheumatology care plans and expressed a desire to learn more about the subject8. This offers an important opportunity for more meaningful and culturally relevant care for Indigenous Peoples with arthritis moving forward. However, the researchers found that respondents generally expressed a “colonial construct of medicine and healing” in which western bio-medicine is viewed as superior to other healing practices.

One promising model to help address these systemic biases and support Indigenous-led models of care is found in British Columbia where, since 2013, the First Nations Health Authority has assumed responsibility for healthcare planning, management and services for First Nations – services that were previously delivered by Health Canada. Serving the over 200 First Nations in BC, as well as those in urban centers, it delivers culturally safe and appropriate approaches to wellness that embody First Nations’ principles of wellness.

A path forward

Meaningful, equitable, and ongoing investments in Indigenous-led and community-based health and wellness care are essential to close the gap in arthritis health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples in Canada. This is reflected in Calls to Action #18 from the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission: “We call upon the federal, provincial, territorial, and Aboriginal governments to acknowledge that the current state of Aboriginal health in Canada is a direct result of previous Canadian government policies, including residential schools, and to recognize and implement the health-care rights of Aboriginal people as identified in international law, constitutional law, and under the Treaties.” 9

By reading, listening, and amplifying Indigenous-led efforts, such as the Calls-to-Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Calls-for-Justice from the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls’ Inquiry, you can support a better health system for all, including Indigenous Peoples.

It’s important to let elected officials know about health inequities in Canada such as those experienced by Indigenous peoples. Your voice matters. Share this information with your MP, MLA, MNN or MPP today.

COVID-19 mortality rates higher in visible minority communities

An increasing amount of research reveals that visible minority communities are suffering more impacts of COVID-19 than the general population in Canada. For example, Statistics Canada recently reported that during the first wave of the pandemic (March-July 2020), residents of neighbourhoods with higher proportions of visible minorities had a higher likelihood of dying from COVID-19 in Canada’s three largest provinces. In some cases, mortality rates were up to three times higher than the general population. *Note that in the definition used by Statistics Canada, Indigenous Peoples are not considered visible minorities.

Researchers have said that more specific race-based data are needed so that these inequalities can be better understood and effectively addressed throughout the country. However, some provinces including British Columbia and Quebec are still not collecting this information.

In Ontario, where specific race-based and income-based data have been collected for several months, findings show that that 80% of cases are happening in visible minorities and 50-60% of cases are happening in low-income households. Dr. Andrew Boozary, executive director of Population Health & Social Medicine at the University Health Network in Toronto, stated: “This isn’t about a deficiency in people or communities. These are structural deficiencies that we’ve allowed to take place because of structural racism, because of structural discrimination toward certain populations.”

In cities where neighbourhood or ethnicity-specific data has been released, it is known which groups have been most affected. In Toronto, the data showed the Black, South Asian, Arab, Southeast Asian and Latin American communities were over-represented among COVID-19 cases. Whites and East Asians were under-represented. It also showed households with incomes under $50,000 to be over-represented among confirmed cases.

Dr. Boozary said the fact that COVID-19 is more prevalent among low-income and racialized communities should not come as a surprise: “When you look at anything from diabetes to cancer to some of the heart and lung conditions that we have, it has always been highly concentrated amongst people living in poverty and in racialized communities. Most everyone in public health could have predicted where COVID was going to be most concentrated because of the structural vulnerabilities, because of the impossible situations that certain populations and neighbourhoods are in.”

Experts have noted that the longer we wait to start collecting this information in provinces like BC and Quebec, the longer it will be until meaningful policy and protections for vulnerability communities can come into place. According to Dr. Boozary: “it’s important to have specific, reliable data so affected populations can be protected.”

Indigenous Communities & COVID-19

In recent months, Indigenous Services Canada has recorded concerning spikes of COVID-19 on many First Nations Reserves across the country including in Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Additionally, a developing outbreak in Nunavut saw cases jump from 0-70 in a matter of days – cases are now being reported within the Territory’s Indigenous communities. There are many social and economic factors that are putting Indigenous communities at higher risk for COVID-19 than the general population. Some important factors include rural/ remote location, over-crowded housing, lack of access to safe drinking water and barriers to accessing health services due to structural racism and social inequalities.

It is important to note that in the first wave of the pandemic the rate of

COVID-19 in First Nations communities were in fact lower than that of the general population in Canada. Researchers have attributed this to Indigenous self- determination, leadership and knowledge; it emphasizes indigenous resilience and the strength of community organization. Indigenous leaders are urging that their communities be supported with the resources needed to flatten the curve once again and that structural inequalities responsible for these outbreaks are meaningfully addressed. As stated by Yukon Regional Chief Kluane Adamek & Manitoba Regional Chief Kevin Hart from the Assembly of First Nations. “The COVID-19 pandemic has reaffirmed First Nations resiliency and our ability to be innovative and support one another. However, it has also magnified the inequities and challenges faced by many First Nations”

There is a great diversity of Indigenous experiences within the healthcare system, especially between the realities of Inuit, Métis, and First Nations (both on-reserve and off-reserve). Despite this, Indigenous patients are often required to navigate multiple systems of care, whether federal, provincial, territorial, or Indigenous run.

The navigation of different health services for First Nations, both on- and off-reserve, whether federal, provincial, or band–run, often results in a complicated, patchwork system that inevitably result in certain individuals falling through the cracks, being forced to pay out of pocket for services guaranteed within Treaty or other constructive arrangements. For example, research has demonstrated healthcare professionals (HCPs) often do not know who pays for what1. This uncertainty has been most evident in the discussions around Jordan’s Principle – a principle that arose from the passing of 5-year-old Jordan River Anderson from Norway House Cree Nation when he did not receive proper care because the governments of Canada and Manitoba could not agree on who should pay for what services.Since this point, Jordan’s Principle has guaranteed that First Nations children receive the necessary care they need, when they need it, with payments worked out afterwards2. Jordan’s Principle has been extended to include Inuit children in the Inuit Child First Initiative.

In terms of access to medications, the non-insured health benefits (NIHB) program provides supplementary health benefits, including prescription and non-prescription drugs, for registered First Nations and recognized Inuit throughout Canada. In Northwest Territories, the NIHB is the only public drug plan3.

In an arthritis context, ACE’s Medications Report Card has shown that the NIHB is not equal to other provincial drug plans. Over the Report Card’s 12-year history, NIHB has consistently ranked at or near the lowest in terms of providing reimbursement for inflammatory arthritis medication.

It is deeply important for non-Indigenous Canadians – including arthritis patients, researchers and healthcare providers – to have an understanding of Canada’s colonial history and its ongoing legacy, the land that we live on, and current issues facing Indigenous Peoples. To learn more about these topics outside of this JointHealth™ insight:

|

| Your voice is powerful. While it may feel like these issues are out of your control, there are accessible ways that people living with arthritis can make a difference. |

- Send a letter to your elected officials telling them that these health inequities matter to you. You may advocate for equitable coverage for arthritis drugs under NIHB, or cultural safety for Indigenous Peoples in healthcare settings.

- Participate in one of the 7 campaigns run by the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society that work to improve the health of First Nations Children and youth.

Gaps in health outcomes are not ‘by chance’

Similar findings related to Indigenous health outcomes in other countries with a history of settler colonialism show us that these imbalanced outcomes are a symptom of a broader problem and violence against Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous Peoples in Aotearoa/New Zealand, the United States, Canada, and Australia all experience higher prevalence and severity of arthritis, higher rates of hospitalizations but fewer visits to specialists than the non-Indigenous population. More specifically, researchers from the University of Calgary found that Indigenous populations had up to 50% fewer visits to specialists than non-Indigenous populations (In Canada and Aotearoa/New Zealand), but up to 300% more hospitalizations due to arthritis complications (in Canada, Aotearoa/New Zealand and the United States6).

Indigenous models of care

In the development of a First Nations-centric perspective on healthcare, the Assembly of First Nations worked with Elders and Knowledge Keepers to propose a new path forward of health systems under the First Nations Health Transformation Agenda that reflect First Nations and their ways of life: “The Elders have a vision for First Nations health that reflects a wholistic understanding of health that includes physical, emotional, mental and spiritual wellness. This vision is grounded in our nationhood and guided by the sacred principles gifted to us by our ancestors and the Creator7.” This approach to healing is fundamentally different than what is traditionally conceived within ‘mainstream’ healthcare systems.

To demonstrate a wholistic approach to healing, above is a graphic representing the First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum. This comprehensive framework is rooted in the Indigenous social determinants of health, which emphasize First Nations culture as a crucial element to effective health programs and service delivery.

Unfortunately, this worldview is not well-understood or adopted in mainstream rheumatology practices. A recent survey of rheumatologists in Canada found that most respondents (73%) were unclear or unaware of what Indigenous healing practices were but nearly all respondents (93%) were open to the idea of including Indigenous healing practices in rheumatology care plans and expressed a desire to learn more about the subject8. This offers an important opportunity for more meaningful and culturally relevant care for Indigenous Peoples with arthritis moving forward. However, the researchers found that respondents generally expressed a “colonial construct of medicine and healing” in which western bio-medicine is viewed as superior to other healing practices.

One promising model to help address these systemic biases and support Indigenous-led models of care is found in British Columbia where, since 2013, the First Nations Health Authority has assumed responsibility for healthcare planning, management and services for First Nations – services that were previously delivered by Health Canada. Serving the over 200 First Nations in BC, as well as those in urban centers, it delivers culturally safe and appropriate approaches to wellness that embody First Nations’ principles of wellness.

| Travelling consultations, telehealth, and virtual care are also beneficial to Indigenous Peoples that live in rural communities. In this #CRArthritis interview, Dr. Nima Shojania, a rheumatologist in BC, describes his experience with travelling consultations and telehealth in rural communities. Dr. Cheryl Barnabe, a Métis rheumatologist in Calgary, shares her insights with #ArthritisAtHome on healthcare delivery to Indigenous and underserved communities, many of whom are at higher risk of COVID-19 because of underlying medical conditions. She explains the challenges of physical distancing, mental health, and how virtual care is being used in these communities. |

A path forward

Meaningful, equitable, and ongoing investments in Indigenous-led and community-based health and wellness care are essential to close the gap in arthritis health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples in Canada. This is reflected in Calls to Action #18 from the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission: “We call upon the federal, provincial, territorial, and Aboriginal governments to acknowledge that the current state of Aboriginal health in Canada is a direct result of previous Canadian government policies, including residential schools, and to recognize and implement the health-care rights of Aboriginal people as identified in international law, constitutional law, and under the Treaties.” 9

By reading, listening, and amplifying Indigenous-led efforts, such as the Calls-to-Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Calls-for-Justice from the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls’ Inquiry, you can support a better health system for all, including Indigenous Peoples.

It’s important to let elected officials know about health inequities in Canada such as those experienced by Indigenous peoples. Your voice matters. Share this information with your MP, MLA, MNN or MPP today.

| ACE is committed to learning from and listening to members of its community If you have feedback on this article, or, if you have witnessed or personally faced discrimination during your experiences as an arthritis patient, researcher or healthcare professional, please consider sharing your experiences by emailing feedback@jointheath.org. Your input will help inform advocacy work in this area. |

COVID-19 mortality rates higher in visible minority communities

An increasing amount of research reveals that visible minority communities are suffering more impacts of COVID-19 than the general population in Canada. For example, Statistics Canada recently reported that during the first wave of the pandemic (March-July 2020), residents of neighbourhoods with higher proportions of visible minorities had a higher likelihood of dying from COVID-19 in Canada’s three largest provinces. In some cases, mortality rates were up to three times higher than the general population. *Note that in the definition used by Statistics Canada, Indigenous Peoples are not considered visible minorities.

Researchers have said that more specific race-based data are needed so that these inequalities can be better understood and effectively addressed throughout the country. However, some provinces including British Columbia and Quebec are still not collecting this information.

In Ontario, where specific race-based and income-based data have been collected for several months, findings show that that 80% of cases are happening in visible minorities and 50-60% of cases are happening in low-income households. Dr. Andrew Boozary, executive director of Population Health & Social Medicine at the University Health Network in Toronto, stated: “This isn’t about a deficiency in people or communities. These are structural deficiencies that we’ve allowed to take place because of structural racism, because of structural discrimination toward certain populations.”

In cities where neighbourhood or ethnicity-specific data has been released, it is known which groups have been most affected. In Toronto, the data showed the Black, South Asian, Arab, Southeast Asian and Latin American communities were over-represented among COVID-19 cases. Whites and East Asians were under-represented. It also showed households with incomes under $50,000 to be over-represented among confirmed cases.

Dr. Boozary said the fact that COVID-19 is more prevalent among low-income and racialized communities should not come as a surprise: “When you look at anything from diabetes to cancer to some of the heart and lung conditions that we have, it has always been highly concentrated amongst people living in poverty and in racialized communities. Most everyone in public health could have predicted where COVID was going to be most concentrated because of the structural vulnerabilities, because of the impossible situations that certain populations and neighbourhoods are in.”

Experts have noted that the longer we wait to start collecting this information in provinces like BC and Quebec, the longer it will be until meaningful policy and protections for vulnerability communities can come into place. According to Dr. Boozary: “it’s important to have specific, reliable data so affected populations can be protected.”

Indigenous Communities & COVID-19

In recent months, Indigenous Services Canada has recorded concerning spikes of COVID-19 on many First Nations Reserves across the country including in Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Additionally, a developing outbreak in Nunavut saw cases jump from 0-70 in a matter of days – cases are now being reported within the Territory’s Indigenous communities. There are many social and economic factors that are putting Indigenous communities at higher risk for COVID-19 than the general population. Some important factors include rural/ remote location, over-crowded housing, lack of access to safe drinking water and barriers to accessing health services due to structural racism and social inequalities.

It is important to note that in the first wave of the pandemic the rate of

COVID-19 in First Nations communities were in fact lower than that of the general population in Canada. Researchers have attributed this to Indigenous self- determination, leadership and knowledge; it emphasizes indigenous resilience and the strength of community organization. Indigenous leaders are urging that their communities be supported with the resources needed to flatten the curve once again and that structural inequalities responsible for these outbreaks are meaningfully addressed. As stated by Yukon Regional Chief Kluane Adamek & Manitoba Regional Chief Kevin Hart from the Assembly of First Nations. “The COVID-19 pandemic has reaffirmed First Nations resiliency and our ability to be innovative and support one another. However, it has also magnified the inequities and challenges faced by many First Nations”

| 1 | Wylie, L., McConkey, S., Corrado, A.M. (2019) Colonial Legacies And Collaborative Action: Improving Indigenous Peoples’ Health Care in Canada. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 10(5) doi: https://ojs.lib.uwo.ca/index.php/iipj/article/view/9340 |

| 2 | Assembly of First Nations. Jordan’s Principle. https://www.afn.ca/policy-sectors/social-secretariat/ jordans-principle/ |

| 3 | Government of Canada (2020). Non-Insured Health Benefits: Drug benefit list https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/ 1572888328565/1572888420703 |

| 4 | Thurston, W.E., Coupal, S., Jones, C.A. et al (2014). Discordant indigenous and provider frames explain challenges in improving access to arthritis care: a qualitative study using constructivist grounded theory. Int J Equity Health, 13 (46) https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-13-46 |

| 5 | Adam Laskaris (June 24, 2020). “Blood alcohol guessing game offers window into anti-Indigenous racism in healthcare”. WindSpeaker. https://windspeaker.com/news/windspeaker-news/blood-alcohol-guessing-game-offers-window-anti-indigenous-racism-healthcare |

| 6 | Loyola-Sanchez, A., Hurd, K., & Barnabe, C. (2017). Healthcare utilization for arthritis by indigenous populations of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States: A systematic review*. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism, 46(5), 665–674. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0049017216301664?via%3Dihub |

| 7 | The Assembly of First Nations (2017). The First Nations Health Transformative Agenda. ELDERS AND KNOWLEDGE KEEPERS’STATEMENT ON THE HEALTH ACCORD. P1. |

| 8 | Logan, L., McNairn, J., Wiart, S., Crowshoe, L., Henderson, R., & Barnabe, C. (2020). Creating space for Indigenous healing practices in patient care plans. Canadian medical education journal, 11(1), e5–e15. https://doi.org/10.36834/cmej.68647 |

| 9 | Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (2015). |

Listening to you

We hope you find this information of use. Please tell us what you think by writing to us or emailing us at feedback@jointhealth.org. Through your ongoing and active participation, ACE can make its work more relevant to all Canadians living with arthritis.

Update your email or postal address

Please let us know of any changes by contacting ACE at feedback@jointhealth.org. This will ensure that you continue to receive your free email or print copy of JointHealth™ insight.

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE)

Who We Are

Arthritis Consumer Experts (ACE) operates as a non-profit and provides free research based education and information to Canadians with arthritis. We help (em)power people living with all forms of arthritis to take control of their disease and to take action in healthcare and research decision making. ACE activities are guided by its members and led by people with arthritis, scientific and medical experts on the ACE Advisory Board. To learn more about ACE, visit www.jointhealth.org

Disclosures

Over the past 12 months, ACE received grants- in-aid from: Arthritis Research Canada, Amgen Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canadian Rheumatology Association, Eli Lilly Canada, Hoffman-La Roche Canada Ltd., Knowledge Translation Canada, Merck Canada, Novartis Canada, Pfizer Canada, Sandoz Canada, Sanofi Canada, St. Paul’s Hospital (Vancouver), UCB Canada, and the University of British Columbia.

ACE also received unsolicited donations from its community members (people with arthritis) across Canada.

ACE thanks funders for their support to help the nearly 6 million Canadians living with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and the many other forms of the disease.

Disclaimer

The material contained on this website is provided for general information only. This website should not be relied on to suggest a course of treatment for a particular individual or as a substitute for consultation with qualified health professionals who are familiar with your individual medical needs. Should you have any healthcare related questions, you should contact your physician. You should never disregard medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this or any website.

This site may provide links to other Internet sites only for the convenience of World Wide Web users. ACE is not responsible for the availability or content of these external sites, nor does ACE endorse, warrant or guarantee the products, services or information described or offered at these other Internet sites.

Although the information presented on this website is believed to be accurate at the time it is posted, this website could include inaccuracies, typographical errors or out-of-date information. This website may be changed at any time without prior notice.